Why is someone who crosses a picket line called a scab? The insult goes back to the 1500s, when “scab” had come to mean a low, mean, rascally person—a scoundrel.

Strikes themselves are far older than most people assume. One of the earliest recorded strikes happened in Ancient Egypt in 1152 BC, when artisans of the Royal Necropolis at Deir el-Medina stopped work because the government of Ramesses III had not properly paid their wages. They were actually successful and their pay was raised. These were small and localized actions, but they show the basic logic of a strike: workers may not have much power individually, but they can cause real pressure by refusing to work.

Other early labor stoppages and mass protests appear throughout history. They did not always work out. In AD 271, workers at the imperial mint of Emperor Aurelian reportedly resisted his attempts to reform the currency, and the conflict ended brutally when troops were sent in and many people were killed. Whether peaceful or violent, these examples show the same underlying point: labor has leverage, and authorities have often been nervous about it.

Striking grew alongside the creation of guilds for different trades, but it only really took off once the Industrial Revolution began. Factories were rapidly being created, and workers were moving from the countryside into towns. Conditions were harsh, pay was low, and workers were often treated as disposable. But workers also realized something important: if they downed tools, the owner started to lose money immediately. The popularity of striking as a tool of negotiation grew, and so did the language used to shame anyone who undermined it.

“Scab” is an inherited English word. It goes back to Old English “sceabb,” meaning an itchy skin disease like mange/scabies, and it has close Scandinavian relatives (Old Norse “skabb”) that likely helped shape later forms. In surviving texts, the noun is recorded in Middle English by about 1250 with the “skin disease” sense, and by the late 1300s it had broadened from the disease itself to the raised patches and crusts associated with it. By around 1400, “scab” could mean the hard covering that forms over a wound.

Then, in the 1500s, the meaning took another leap. “Scab” became a term for a low or contemptible person. One reason is simple metaphor: visible scabs suggest disease, and disease has long been tied (fairly or unfairly) to ideas of dirtiness and moral failure. In the same period, early modern writing sometimes used “scab” language as a euphemism in talk about venereal disease, which may have added extra force to the insult. Another possibility is that similar slang existed in other European languages and reinforced the meaning in English. Either way, “scab” became a convenient word for someone society wanted to despise.

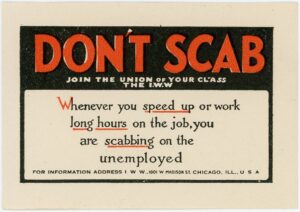

It wasn’t a great leap to apply that contempt to labor disputes. A strike only works when workers stick together, because the goal is to make the employer feel the pain of lost production. The person who crosses a picket line helps the employer keep operating and weakens the strike’s bargaining power. Calling that person a “scab” frames them as contaminated and untrustworthy, someone who should be avoided.

The word also works as a metaphor in a second way. A real scab is a crust that forms after damage. It can protect a wound while it heals, but it can also be a sign of infection or irritation, and it can hide what is happening underneath. For union members, a strike is a kind of collective “wound” in the relationship between workers and management. A strikebreaker becomes the crust that covers the damage and stops it from healing properly, because the underlying problem is never forced into the open.

The earliest recorded use of “scab” with the meaning “strikebreaker” is July 5th, 1777, in Bonner & Middleton’s Bristol Journal, reporting on a shoemakers’ dispute. The notice complained that “The Conflict would not [have] been so sharp had not there been so many dirty Scabs.” That line is striking because it sounds casual, as if readers would already understand the insult. It may have been the first time it appeared in print, but it probably wasn’t the first time it was said.

As industrial action became more common, the meaning of “scab” broadened again. It could mean a person who crossed the picket line to keep working, but it could also mean someone who refused to join the union at all. In that mindset, a scab was a traitor: someone benefiting from better wages or conditions without taking any of the risk, and someone weakening the solidarity that made collective bargaining possible in the first place. (Other English-speaking countries also used different slurs for strikebreakers, like “blackleg,” but “scab” has remained the most famous.)

The uglier side of this is that “scab” has always been meant to scare people into compliance. Strikebreakers have often needed police escorts to enter workplaces, and they have sometimes been threatened, harassed, or attacked. Even now, the word still flares up during modern strikes, especially online, where accusations can spread quickly and reputations can be targeted. When the Writer’s Guild of America went on strike in 2023, they had a website where fans could report scabs who were still going in to work. And this is what I learned today.

Sources

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Strike_action

https://www.etymonline.com/word/scab

https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/scab

https://www.huffpost.com/entry/scab-labor-strike-word-origin_l_64c58e54e4b03d9b515bae1c

https://www.teenvogue.com/story/what-is-a-scab-actors-workers-cross-picket-line

https://www.mentalfloss.com/article/12690/why-are-people-who-cross-picket-lines-called-scabs

image By Possibly Ralph Chaplin – I.W.W. “stickerette” or “silent agitator”, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=85509804