How does projection mapping work? Projection mapping works by using very powerful projectors and software that can map the shapes and angles of the object to be projected upon.

You may need two things to do projection mapping. The first is an incredibly powerful projector, or several very powerful projectors for larger venues. The power of a projector is measured in lumens, which is the measurement of the amount of light visible to the human eye. 1 lumen is roughly the amount of visible light put out by one birthday candle. A regular candle puts out about 12 lumens. A lot of LED lights are measured in lumens these days, and an average room light might have 600 lumens, which is bright enough to light the whole room. Projectors have to be more powerful than that. A general commercial projector that you might have in your house or a classroom will probably be in the order of 3,000 lumens. That is bright enough to see on a screen if the projector is about 5 meters away and the room is dark. If you want to project something onto the side of a building with reasonable brightness and clarity, you are going to need 50,000 or more lumens. Some of the most powerful projectors can approach 100,000 lumens. However, projection mapping usually uses banks of powerful projectors, rather than one of that power. A single projector putting out 100,000 lumens would get far too hot and need too much power. Banks of powerful projectors can be attached to cooling systems and powered independently. You need to ensure that you get enough light per square meter on the building. That either means a closer projector or a more powerful projector.

Other than the difference in brightness, projectors used for projection mapping are almost the same as regular projectors used to project images onto a 2D screen. They have a few differences, such as precise geometry controls and synchronization, but you can do it with a simple projector. The magic all comes from the software. The first step is to map out the size and shape of the building to be projected on. This is the “map” part of projection mapping. There are a few ways to map the building: laser scanning, photogrammetry (building a 3D model from photos), or camera-assisted/manual alignment. Using a digital camera is the easiest way and doesn’t require any specialist equipment, but it will never be quite as accurate as a laser. Using a photo is the easiest way to get started, but you usually still have to help the software by placing points, drawing guides, or manually aligning a grid to match the building. A laser is far more accurate. To do this, you need a scanning laser, which you set up on a tripod. The laser rotates, bouncing light off the building and timing how long it takes to come back. You have to do this in several different locations, but when you are finished, you will have a very accurate map of the façade of the building you are going to use.

Once you have the layout of the building to be projected upon, the next step is to fit the pictures or video to it. Some types of software will analyze the image automatically and draw lines and grids. For some types of software, it needs to be done manually. There are two ways of approaching the mapping, and that depends on where you are going to have your projector. If you have a projector that you are not going to move, you only need to map the 2D front of your building. If you are going to move the projector, then a 3D map helps a lot, but you still need a way to recalibrate or track the projector’s position. If you only have a 2D setup and you move your projector even a tiny bit, everything will go out of line. If you want true depth to your projection, then you are going to need a 3D image because you will want to put something on all of the areas.

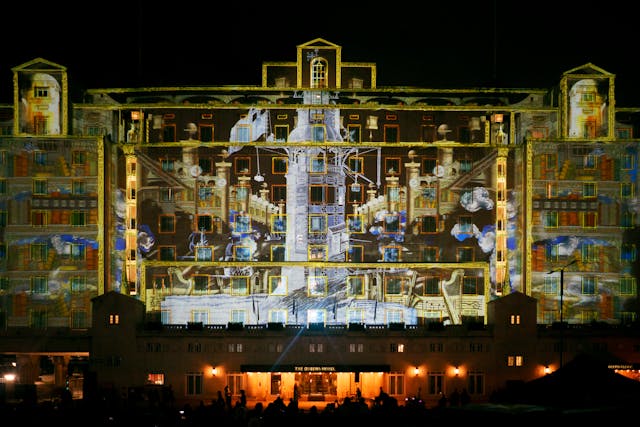

Once you have the map, you just need to cut up the video or the images into sections and align each section with its position on the image. You also need to mask out windows and edges so you don’t project light onto areas where you don’t want it. If you separate out the different parts of the building properly, then the software will be able to treat them differently, and you can have effects where images appear to move around the physical features of your building, such as pillars.

Projection mapping is very common now, but early versions of the idea were already appearing by the late 1950s. A Czech designer called Josef Svoboda used large-scale projected imagery at Expo 58 in Brussels, and people sometimes describe this kind of work as ‘painting with light’. Disneyland’s Haunted Mansion in 1969 is often cited as the first true use of projection mapping. They didn’t have the computing power and the software that are available now, so they had to use carefully positioned projectors. Now, the technology is so advanced that people can project an image onto their house with very little training and at a relatively low cost. And this is what I learned today.

Sources

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Projection_mapping

https://www.heavym.net/what-projection-mapping-is-and-how-to-do-it

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lumen_(unit)

https://energyeducation.ca/encyclopedia/Lumen

Photo by Howard Senton: https://www.pexels.com/photo/artistic-projection-on-the-queens-hotel-leeds-30726291/