How does a naval mine work? There are several different kinds of mine that are intended for different targets and there are several different detonation mechanisms depending on the age of the mine and the cost.

Naval mines have existed since explosives were discovered. The first naval mines were used in China in the 14th century. These mines were wooden boxes full of explosives and carrying a timed charge that were allowed to drift among enemy ships. They were very effective. Mine technology improved over the centuries and their worth was demonstrated again and again in wars. They were used extensively in World War 1 and it is estimated that 235,000 naval mines were laid during the war. During World War 2, over half a million naval mines were laid.

There are several different types of mines, and they are aimed at different types of shipping. There are regular mines that stay at the surface. They are general mines targeted at any shipping. There are mines that are floated at different depths to target heavier ships, such as aircraft carriers, thereby avoiding smaller ships. There are mines that are kept close to the bottom of the sea and they mostly target submarines.

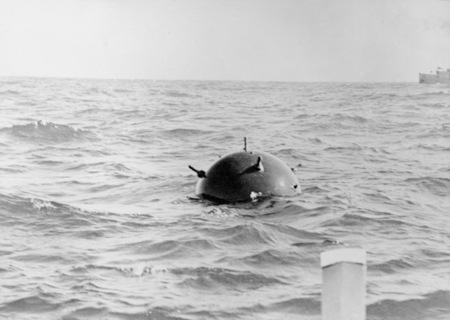

The most common and the cheapest kind of mine is the contact mine. They are metal balls that float at the surface of a little below the surface. They have the shape that we recognize from the movies as a naval mine. That is, they have a lot of “spikes” coming off them. Those spikes are called “Hertz horn” and they are the detonator for the mine. Each Hertz horn contains a glass vial filled with sulfuric acid. The Hertz horns are hollow tubes that run down into the center of the mine. There is a lead-acid battery in the center of the mine, connected to the explosive. The battery has no acid electrolyte, which means it cannot make power. When a ship hits the mine, it breaks one or more of the Hertz horns, breaking the glass vials and sending the sulfuric acid down the tube and into the battery. The acid becomes the electrolyte, and the battery turns on, detonating the explosive. These mines are usually tethered to the bottom of the sea because it is too dangerous to have free drifting mines. Some countries have experimented with free drifting mines, but there is no way of knowing where they will go and no way of getting them back after the war is over.

Another type of mine was developed during the Second World War and was aimed at submarines. An explosive device was weighted down to the seafloor. A copper cable from the device was attached to a buoy and floated directly above the explosive. If a submarine’s metal hull came in contact with the copper wire, it would make a small voltage change, which would detonate the explosive.

A third type of mine is known as a limpet mine because they stick to ships or submarines. They are naval mines, but they have to be attached to the target by hand. Their powerful magnets keep the mine attached to the ship until the explosive is detonated.

The problem with contact mines is that they are fairly cheap and very easy to make. Hundreds of thousands of mines have been set in the seas over the 20th century. Many of these have been cleared, but there are still mines from the wars floating in the sea and ships collide with them occasionally. Minesweeping in the sea is a very difficult and expensive task. It costs far more clear a mine that it does to plant one and most countries don’t have any incentive to try and clear them.

Modern mines are far more sophisticated, and they are able to deactivate themselves after a specific period of time. This technically makes them safer, although, on the other hand, they have more antitampering mechanisms which makes them extremely difficult to clear up.

Traditional mines are activated by contact with a ship. Modern mines have far more sensors and onboard computers. They can be set to detonate on a particular acoustic signal. All ships sound different because of their size and their engines. Mines can be programmed to detonate on a specific acoustic signal, which means it is safe for friendly boats to sail through the minefield, but if the boat with that acoustic signal gets close, the mines will detonate. These mines can be contacted and have their programming updated, allowing them to target different boats. They also have counters onboard. The first two or three ships in a convoy could be minesweepers, or more expendable small ships. The target is always the valuable ships in the middle of the convoy: the aircraft carriers, or oil tankers. A naval mine with a counter can ignore the first three of four ships that pass and then detonate on the next one. Mines, as with all military equipment, are rapidly becoming more technological. And this is what I learned today.

Sources

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Naval_mine

https://www.history.navy.mil/browse-by-topic/exploration-and-innovation/naval-mine-warfare.html]